Queenie's Peach Cobbler/Looking at the World through Cast Iron Lenses

That is, when you go to a restaurant or perhaps to dinner at a friend’s house, do you think when the food is served, “You know, I bet this would taste even better if it were cooked in cast iron”?

I admit I do this. In fact, when I make old family recipes, I chuck the directions to use a glass dish, and I usually cook in cast iron instead. You think that green bean casserole is good in a Pyrex dish? You’ve not had green bean casserole until you’ve had it cooked in cast iron. If skillet fries taste best in cast iron, think of how good your uncle’s hash brown casserole will taste. I’ve got two cast iron pans specifically for casseroles, but if you don’t, a cast iron skillet will work just as well.

My cast iron

Of course, I should point out that I never actually ate this peach cobbler at my grandmothers house when she was alive. But my mother made it regularly and always referred to it as her “Mom’s Peach Cobbler.” In the copy of the recipe I received, which had the title just mentioned at the top of the page, the directions simply called for a “casserole” dish. But this goes back to my previously mentioned point—I was certain this would go better in cast iron!

In fact, the recipe itself isn’t all that different from the cobblers we’ve made while camping, using a dutch oven placed directly on top of live coals. One of the best features of those great campout cobblers is the crust that forms in the cast iron. Therefore, I was fairly certain that I could (forgive me for saying this!) improve on my grandmother’s recipe.

At our church, my Sunday school class has a potluck brunch every first Sunday of the month. So two weeks ago, I decided to make my grandmother’s peach cobbler, but not in a glass dish, but in cast iron! Now, my wife, Kathy, who doesn’t like peaches (odd, isn’t she?), asked if I’d also make one using apples instead. The recipe is pretty versatile, so the picture at the beginning of this post has apple on the left and peach on the right. To make the cobbler even more special, I made the original peach recipe specifically in my grandmother’s skillet that was handed down to me years ago. It is a BS&R and is at least 70 years old if not older. I used my Lodge skillet that I got in the nineties for the apple cobbler.

Needless to say, both cobblers were a hit, but the peach cobbler was completely gone when the apple cobbler was only half eaten. But by the end of our class, both pans were empty. Cast iron is definitely superior to the standard casserole dish for this recipe as you probably imagine. I encourage you to join me in looking at your world through cast iron lenses!

So, here is Queenie’s recipe for peach cobbler. It’s very easy, so very basic and so very good. Enjoy!

Queenie’s Peach Cobbler

10.25" Cast Iron Skillet

Ingredients:

- 1 stick butter

- 1 cup of sugar

- 1 cup of flour

- 1/4 teaspoon of salt

- 2 teaspoons of baking powder

- 1 cup whole milk

- 1 can of sliced peaches, don't drain

Melt a stick of butter in a cast iron skilet.

Mix a cup of sugar, a cup of flour, 1/4 teaspoon salt, two teaspoons of baking powder, 1 cup whole milk.

Pour in 10.25" cast iron skillet and add one large can of sliced peaches (don’t drain).

Bake at 350° 30-40 minutes.

Rick plans to post more of his grandmother’s recipes in the future, so check back often. Feel free to leave your thoughts or ask questions in the comments below, or you can contact Rick directly at rick@cookingincastiron.com.

Coming to Terms with Pre-Seasoned Cast Iron

If you have many discussions with true cast iron aficionados, you may find a wide variety of opinions on a number of subjects: the “proper” method for seasoning cast iron, soap or no soap when cleaning, old cast iron vs. new cast iron, and much more. But if you really want to start an argument in some circles, bring up the subject of manufacturer pre-seasoning. For the uninitiated, there was once a day when all “new” cast iron came gun metal gray. Nowadays, that’s almost impossible to find because nearly all new cast iron comes already nice and black since it’s been “pre-seasoned” from the manufacturer, usually with a sprayed on vegetable oil concoction.

And for the extremely uninitiated, when someone refers to seasoning in cast iron circles, it’s a reference to the black coating that builds up overtime on a cast iron pan. This coating, or patina, is the product of the carbonization of oils and creates a natural non-stick surface on a pan. This is why a cast iron skillet or other pan actually improves with age as opposed to chemically treated non-stick pans which generally get worse as they get older.

I just ran an informal inventory of our cast iron. We have roughly 29 cast iron cooking items, or 30 if you count my Sportsmans Grill. In that count, I’m not including lids (even though I bought at least one separately) or novelty items such as the little ashtray-size skillet that we use for a spoon rest. With a couple of exceptions, all of our cast iron items are pans we actually use on a fairly regular basis. In other words, we don’t get into collecting cast iron for the sake of collecting. I’m not knocking that, mind you; nor am I saying I’d never do that. We simply don’t have the room for that right now.

Now of the 29 or 30 cast iron items we have, 16 came pre-seasoned from either Lodge or Santé. But that wasn’t always the way it was. My first piece of cast iron was a Lodge 10.25” skillet given to me in the mid-nineties by my mother. it came completely unseasoned, so I had to season it myself. I can’t remember what kind of oil I used on that first attempt, but I do recall that it was a disaster. Through trial and error, I eventually got it right. As many of you can no doubt relate, the more I used that cast iron skillet, the more I wanted to use cast iron for just about all my cooking. My second cast iron item was obvious. I needed a dutch oven to cook my gumbo. Somehow, I just instinctively knew gumbo would taste better in cast iron--and I was right!

I requested a dutch oven for Christmas and I received TWO that were exactly the same with one exception. One was pre-seasoned and one was not. As pre-seasoned cast iron really just came into vogue in the early part of this decade, many companies at the time offered both pre-seasoned and bare items side-by-side in the same stores. Seeing pre-seasoning as a bit of a novelty, and remembering my initial experience with my skillet, I opted to keep the pre-seasoned dutch oven and sell the bare cast iron dutch oven. I later regretted this decision.

What’s the big deal with pre-seasoning? Well, it tends to eventually come off the pan. Take for example, the lid pictured below of my Lodge 2 qt. Serving Pot

You can see how faded the pre-seasoning has become. Believe it or not, that was after only two uses! I’ve re-seasoned it myself since, and it’s doing fine. I’d also point out that in my experience, a pre-seasoned pan doesn’t normally lose its seasoning quite so quickly. But this is typical of what often happens eventually to a pre-seasoned cast iron pan. And if it doesn’t fade, the pre-seasoning chips off. Of course, pre-seasoning is not dangerous to someone’s system as a chemical non-stick surface like Teflon might be. In fact, the pre-seasoning treatment that Lodge uses is even certified Kosher!

Nevertheless, when pre-seasoning began to fade or chip in the past, I used to get very frustrated. I really felt (and still do) that I can season a pan better myself. But try finding a major cast iron brand that still offers pans that aren’t pre-seasoned. They’re near non-existant. Now my frustration is fairly mild compared to some. Since Lodge has decided to no longer sell non-pre-seasoned pans, I’ve actually heard some folks say they’ll never buy Lodge again. In my opinion, this is extreme, although no one can argue with the cooking ability of a 100-year-old Griswold skillet or other older pan which becomes the only other alternative to pre-seasoned pans.

Regardless, my frustration with pre-seasoning has become a thing of the past. Yes, I’d rather season a pan myself, but I’ve come to terms with pre-seasoning, and my acceptance has come for a number of reasons.

1. Pre-seasoned pans aren’t really a new innovation.

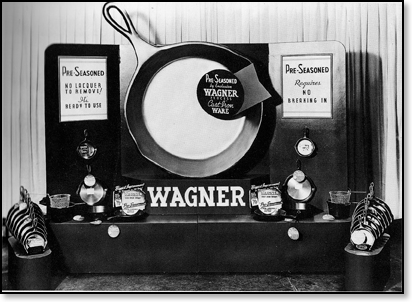

Not too long ago, I was looking through Smith & Wafford’s The Book of Wagner & Griswold (the red book) when something very interesting caught my eye in this photograph below on p. 9.

There’s no date on the picture, but I would guess that it was from the 1940s or 50s, if not earlier. Notice the advertising on these Wagnerware pans. The main selling point for these pans is that they were pre-seasoned. Thus, I find it hard to throw stones at any cast iron company that pre-seasons today--whether that’s Lodge, Camp Chef/Santé, RangeKleen or any other company--because evidently, the idea’s been around for quite a while. Who knows if your prized decades-old skillet that you obtained second hand wasn’t pre-seasoned to begin with!

2. All regularly used cast iron will (probably) have to be re-seasoned.

Let me offer a lesson I learned from my grandmother’s skillet. When my grandmother moved into an assisted living home a few years back, I inherited her 10.25” skillet pictured below.

I don’t know exactly how old this skillet is. My grandfather tells me she had it their entire married life. They were married 71 years before she died in 2008. If it was brand new when they got married, it’s well over 70 years old. But if it was a hand-me-down, it’s much older. I have no idea what brand it is. It only says “NO. 7" and "10 1/4 IN.” on the back. It’s my prized possession of all my cast iron simply because it was my grandmother’s. If you told me I could only keep one piece of my cast iron, I would pick this one--even though I use it second to my Lodge skillet that was my first cast iron pan. Furthermore, when I received this skillet, it honestly had the nicest seasoning I’ve ever seen on any piece of cast iron. The inside bottom is as smooth as glass. I wish I could sit down and talk to my grandmother about this pan, but of course, I can’t now.

Now, you need to know that I take really good care of my cast iron. I never wash with soap. I treat every pan with a fresh coat of olive oil to prepare it for its next use. I never stack pans, and I’m very careful to avoid metal utensils when cooking in them.

However, one day I noticed that my grandmother’s pan was starting to lose its seasoning on the inside bottom. I was shocked! How could this happen? Then guilt set in. I felt embarrassed, ashamed. Knowing that there is no heartache in heaven, I at least found some relief in the fact that she didn’t know.

The reality is, though, that more than likely she had to re-season her pan every now and then. Granted, she and I used her pan differently. She probably didn’t cook overly acidic foods in her pan like chicken marsala (which uses red wine), and I don’t remember her cooking spaghetti sauce all that often in her skillet. Further, while I primarily use olive oil in my pan and occasionally bacon grease; my grandmother primarily used bacon grease, and if she wasn’t using that, she was probably using Crisco!

She also used her pan multiple times a day back and forth between the stovetop and the oven. In the morning, bacon and eggs were cooked for the whole family. She might use it at lunch as well. Sometime in the afternoon, the pan was used for cornbread, cooked in the oven. Then, in the evenings, it was used again for the family dinner. This constant use, multiple times a day, going back and forth between the stovetop and her oven, was incredibly “healthy” for this skillet. And frankly, none of my pans gets this kind of constant use. But I am firmly convinced that this back and forth between the stovetop and oven was a key for keeping such a quality seasoning on the pan.

Since I had to partially re-season my grandmother’s pan (I only concentrated on the inside bottom, using lard for seasoning), I’ve stopped using it for overly acidic foods. But the main point here is that even the best of pans--pre-seasoned or not--have to be re-seasoned every now and then.

3. Pre-seasoning gives folks new to cast iron a head start.

That statement isn’t original to me, and I wish I could find the source. But I remember reading those words one day on someone’s website, and it all just kind of fell into place for me. For many “modern” cooks, bare cast iron can be a real challenge. I know it was for me, but I fell in love with cast iron and was determined to persevere. But with people’s busy schedules, it’s easier for many folks to simply grab a chemically treated non-stick pan, especially if a cast iron pan is going to necessitate a lot of preparation beforehand. I’ve said it before, but I’m firmly convinced that whether one likes pre-seasoning or not, its mainstream use today has been a major factor in the cast iron renaissance that we have witnessed as home cooks (and many professional chefs and celebrity chefs) have realized grandma was right to begin with and have returned to using cast iron.

Further, when I was in South Pittsburg, Tennessee, touring the Lodge Manufacturing plant last summer, I asked a Lodge employee why they no longer offered bare cast iron. Her answer was rather interesting. She said that for a while they offered both. But she said that when put side-by-side on store shelves, the pre-seasoned iron outsold the bare iron by a wide margin. And when their pre-seasoned cast iron sold out, they found that customers would buy other brands that were pre-seasoned over their bare cast iron offerings. That was enough of an answer to make sense to me. Lodge is the last American foundry in existence. I don’t exclusively use their cookware, but I use a lot of it, and I’d hate to ever lose them the same way that other great cast iron companies disappeared over the last few decades.

Two Suggestion for Cast Iron Manufacturers

- Most cast iron cookware comes with a brief set of instructions for care and maintenance. I feel it would be a good idea to also include instructions for re-seasoning cast iron in case the pre-seasoning fades or flakes. Lodge includes re-seasoning instructions on their website, but it might not be a bad idea to include them with the product as well. I shudder to think of perfectly good pans getting thrown out, but I bet it happens.

- Since Lodge is the only cast iron company with a US factory, they might be the only ones who could actually implement this second suggestion. I think it would be a great idea if those of us who prefer bare cast iron were allowed to special order it and have a pan taken from the line before it has the pre-seasoning process applied. Although it seems a bit backwards when I really think about it, I would actually be willing to pay a few dollars more to be able to place a special order and receive my cast iron bare. Then I could season it myself.

Feel free to leave your thoughts or ask questions in the comments below, or you can contact Rick directly at rick@cookingincastiron.com.

The Perfect Stew for Our Crew

One of the advantages of growing up in a large, close-knit family is the access it provides to a variety of activities. The creativity that drives siblings (of any age) in these situations can be inspiring! I recall distinctly the nearly-annual festivity of cooking Brunswick stew in a 30 gallon cast iron pot with my father’s clan. When I say clan, I refer to my grandparents, my uncles and their families, my grandparents’ siblings, and my immediate family. Friends would also drop in over the years for this special cookout. The family would spend days in preparation for this event purchasing the ingredients and preparing them. Whole chickens, hens, pork loins, ground beef, tomatoes, corn, onions, ketchup, hot sauce, Worcester sauce, and other top-secret ingredients would be stockpiled in the kitchen and then guarded carefully until the moment they were prepared for entry in the tremendous pot.

There were particular rules that governed the entire process related to creating this stew. No one under the age of 35 was allowed to stir the pot, although the simmering process would continue for hours and hours. Only a few (rare) exceptions were ever made to this rule to my knowledge. The rationale behind the age limitation was never fully explained, but the best I could conjecture was that 35 marked a level of maturity in which an individual could be found willing to remain still long enough to contemplate the intermingling of flavors occurring in the pot over long periods of time without interruption.

Only the "elder" of the patriarchs of the family hold the knowledge of the top-secret recipe. I’m confident that my grandmother also knew it, as does my mother, but the family maintains the pretense that only the men know it. My dad has always told us that we could only inherit the recipe if we proved ourselves worthy of keeping its secrets. What might be entailed in proving this worthiness is still a mystery. Perhaps now that I am nearing the age during which I might be permitted to stir the pot, my father will share the criteria for inheriting the recipe even if I cannot yet inherit it.

Once an individual met the selection criteria to be allowed to stir the pot, then even stricter rules were applied to that person’s performance at the pot itself. The concoction had to be stirred continuously and only with designated wooden boat paddles. I also observed that the stirring had to be deep and consistent. The sides had to be regularly scraped in the rounds of the pot. All of these measures ensured an even cooking and no burnt stew. Cooking 30 gallons of stew required devotion, attentiveness, willingness to endure the heat (from the stew and from the summer air), and patience; these qualities, once demonstrated, permitted the stew stirrer to enter into the developing camaraderie of the cooking site.

The men of the family would start well before dawn and prepare the cookware and the cooking site. The fire had to be started and monitored. Once the stew was added to the pot, someone had to be on duty at all times to stir and to keep curious insects away. Often, as the stew was cooking, others would bring in an assortment of meats for barbecuing or smoking. One year, my uncle cooked turkeys on stakes by placing them in charcoal pits and covering them with pails. The meat "sides" (as the stew was the entrée) prompted competition among the family. Over the years, we voted on best barbecue sauce, best dessert, best smoked meat, and so on. Rivals sparred good-naturedly and brainstormed the competition that would take place at the next stew cooking.

By mid-afternoon, the stew had been cooking for at least six hours. The scent alone made passers-by hungry for a sample, if not an entire bowl. It was the time of day when the children were ready to pull off their shoes and commence gnawing if they didn’t get a bowl to themselves. The sliced bread, the sweet tea, the side dishes and desserts all appeared on the tables set up outdoors for picnicking. Utensils, bowls, plates and napkins also found their way to the tables and no sooner had they been placed than a line had formed at the cast iron pot. Huge ladles guided by the chefs themselves served up the delightful feast. Once bowls had been filled, plates were soon piled high with barbecue, potato salad, slaw or whatever sides were available. It didn’t take long for these very same plates and bowls to be emptied and for lines to form once again at the stew pot. I wish I could say I remembered the conversations I had over these delicious bowls of stew, but all I remember is wanting more stew.

When no more space was left inside our bellies, we began the clean-up process. Boxes and boxes of storage bags and storage containers were brought out and stew was ladled into them. As a child, I never had to worry about where this stew went since my family always took home enough to enjoy for the remainder of the year. We would store it in the freezer and reheat it. With every bag, I relived memories of the cookout and family togetherness once again.

As an adult living several states away, I traveled from some distance to come back to this event; I always considered myself fortunate if I found that I could transport even a quart bag back home with me. Now that I’m living much closer again, I’ve found that circumstances have kept the family from holding the event as often. I think fondly of the last cookout a couple of years ago and find myself more nostalgic than usual. Since that last event where over 100 people attended (friends and family), we’ve lost several dear ones and now the event won’t seem quite the same. Still, the tradition remains—a family united over the 30 gallon cast iron pot and the incredible mélange it contained.

Feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments below, or you can contact Leila directly at leila@cookingincastiron.com.

Memories Born Out of Simplicity (Cast Iron Traditions)

A few years ago, as a father of two toddlers, I rebelled against any notion that I should have to get up on a Saturday morning and make breakfast for the family. It was the only day in the week when sleeping-in was plausible. Rising early was required the other six days of the week; why could I not have this one day to experience that simple exhilaration--that one joyous moment--when one wakes up without external prodding.

Amidst my whining and self-complain--because the only one who listens to my complaint is the self--I started to become more reflective. I began to justify my resistance by considering how breakfast was not that important to me when I was a kid. Well, except for breakfast at Grandma’s. The smell and sizzle of ham in the skillet and the eggs--brown eggs from the chickens in the back yard, made-to-order, scrambled or sunny-side-up. Oh, and the toast, with homemade jam and jelly, three or four flavors made from the fruit trees right outside. Waffles, butter, syrup, of course this was only tradition in the sense that we visited Grandma and Grandpa’s one or two weeks out of the year.

It wasn’t only the food, but also listening to the conversation of adults as a child. Grandma shared the neighborhood gossip, recalling early years with siblings, and reminiscing about farm life--the good ol’ days.

That’s one thing about childhood memories: we all have them, and our children will have them too; but it is up to us to influence what positive emotional value they might have. In my reflection I realized I wanted to create some of these memories for my children. Memories born out of simplicity, which my kids could look back to and gain insight about their father, and of traditions they could continue and build upon.

Will I get up early and make breakfast for my kids? Yes, of course I will, and I have nearly every Saturday for the last six years. The Saturday morning event has, along with my recipe for pancakes, undergone a few tweaks as time has gone by. A few months ago I eschewed the anodized-aluminum in favor of a cast iron skillet (just like Grandma’s), and more recently implemented a cast iron griddle. The cast iron probably enhances the memory aspect more for me than for my children. Only time will tell. But for me it connects me to the way my mother and grandmother prepared breakfast and many other meals.

I become reflective again. Is this really making an impact on my kids? Do they take comfort in the ritual? Is there security in the knowing of what to expect when they wake up on Saturday? Do they care? Every once in a while I get a glimpse of a connection. One Friday evening as the kids were headed off to bed, perhaps in a mental lapse, my daughter asked, “What’s for breakfast tomorrow?”

I was almost hurt. “What do you think is for breakfast,” came my retort.

“Oh, tomorrow is Saturday--pancakes and maple links. Yes!”

A smile emerged on my face--she gets it.

Feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments below, or you can contact JT directily at ironman@cookingincastiron.com.

And watch for JT’s Saturday morning pancake recipe in an upcoming post.

Cast Iron Contemplations

Why is it that I found the idea of Cooking in Cast Iron—both the action and the blog—intriguing? Is something in my brain wired differently when it comes to cookware fixation? Do I find cast iron appealing because its austere appearance hints at is pragmatic nature even as its rougher surface glistens from its seasoning? Do I identify with cast iron because it is sturdy and yet ironically (no pun intended) fragile in some respects? How odd it all seemed to be drawing personality comparisons with this humble medium of food preparation.

In fact, I know my friends will both be laughing hysterically upon reading the previous paragraph, and I smile at the thought. During my visit, my friend Caryn took me to a cooking store and we browsed for a good 45 minutes. There was a relatively small end cap in the store devoted to Lodge cookware. I even spotted a cast iron Dutch oven on display, which is a notably larger and more expensive piece. I gazed at the various pieces available and mentally calculated when I would be financially free to indulge myself in the purchase of one following the vacation.

Despite my interest in this particular section in the store, my friend was unmoved and unmotivated to break out any cast iron over the weekend. Again, I pondered the difference in her approach and my own. Is having a favorite cast iron pan akin to having a favorite coffee mug? Is there a psychology behind one’s attachment to the medium?

In the end, perhaps our preferences for method and medium are really products of long-established habits. This evening I heard a song on one of my son’s cartoons that speaks volumes on this issue. The song emphasized that the way you do something doesn’t have to “be by the book.” The characters in the cartoon were cooking, among other things, and were shown improvising when they didn’t have all of the ingredients or all of the necessary components to complete a recipe or task.

Perhaps I am not able to prove this speculation (nor do I really perceive a need to do so at the moment), but I have to wonder if the instruments we cook with define us as much as what we are ultimately preparing and how we go about assembling it . After all, artists and artisans are quite selective about their instruments and implements. These individuals understand the value of the tool to the craft. It only seems appropriate that those developing their skill in cooking would opt to select the best instruments, as well.

Feel free to leave your thoughts in the comments below, or you can contact Leila directly at leila@cookingincastiron.com.